Paper Summary: On the Measure of Intelligence (Chollet 2019)

In this post I am summarising “On the Measure of Intelligence” by François Chollet (2019). I hope this post encourages you to read the full work which you can find here. You can also go to the ARC GitHub page to try out the tasks.

Assumed knowledge

I will try to make the post accessible to a general audience, but in the interest of brevity I can’t explain every concept from scratch. For this post it may be helpful to know about:

- The history of AI.

- The history of measuring intelligence (e.g. Turing Test, psychometrics)

- Modern Artificial Neural Networks and their limitations.

Background and motivation

Most people are familiar with intelligence tests in some form. For some this may be the well known IQ test used as a measure of human intelligence. Those in computing almost definitely know of the Turing test. Introduced in 1950, the Turing test is probably the most well known attempt to verify if an artificial intelligence agent is truly intelligent (as we would informally understand it). For many, this may be as far as you think about the problem of measuring intelligence. François Chollet’s “On the Measure of Intelligence” asks us to think again about the problem, and challenges the implicit assumptions being made by modern AI research about the kinds of tests which will lead to better AI.

In particular Chollet points out that recent breakthroughs in AI performance have been on narrow well defined tasks. The resulting AI is highly skilful. Sometimes performing better than humans. However, this skill is hard coded or “bought” by the accumulation of immense amounts of experience, making it highly sensitive to changes in the conditions of operation. In applications like full autonomous driving or those involving human-robotic interaction, we can’t safely collect data on edge cases, and the environment is constantly evolving. To make progress in these areas, we need new ideas.

Chollet provides an alternative approach to measuring progress in AI which acknowledges the role benchmarks play in improving AI performance, but which values efficient skill-acquisition over skill itself. I believe Chollet’s work is a great entry point for readers interested in the long term improvement of AI and for new researchers (such as myself) to develop their understanding of the limitations of the state of the art.

The work in detail

Chollet makes three important contributions corresponding to the three parts of the work:

- Context and history. A well written summary of the history of defining and measuring intelligence.

- A new perspective. A formal definition of intelligence as “skill-acquisition efficiency” and an outline of the properties a benchmark of intelligence should have.

- A benchmark proposal: the ARC dataset. An initial attempt to design a benchmark to test human and human-like general fluid intelligence.

Context and history

Chollet points out that the field of AI often relies on informal definitions of intelligence and it’s measure (e.g. noisy human judge in the Turing test). Defining a goal precisely along with a measure of progress along that goal is crucial for progress on any topic. Case in point, progress in AI is often measured by beating a previous record in a benchmark which abstracts some real world problem (e.g. ImageNet).

Chollet then discusses previous attempts to define intelligence, and highlights two characterisations which are typical of such definitions of intelligence:

- Focus on task specific skill. i.e. Being an excellent chess player.

- Focus on generality and adaption. i.e. Learning new skills.

These characterisations run parallel to views of the human mind which have been argued about in philosophy for centuries (blank slate vs. human nature). More recently, the AI field shifted from building systems as collections of static components (human nature) from the 50s to 70s to the currently dominant deep ANN approach (blank slate). Neither approach is perfect in isolation, the truth is somewhere in the middle.

Chollet then switches focus to measuring intelligence. Most measures test skill in a particular task. While this can lead to systems with specialised capabilities, it doesn’t measure intelligence (as far as it is a mixture of the two characterisations not merely the first). Chollet explains that confusion about what is being measured (skill vs. intelligence) comes from the assumption that in order to be extremely skilled, you must be good at acquiring skills. Which is true of humans but not machines. Chollet’s important point is that no matter what skill we measure, whether this is complex games (go, StarCraft), or successfully fooling a human in conversation, we will not produce a truly intelligent system. Slightly more formally:

“If intelligence lies in the process of acquiring skills, then there is no task X such that skill at X demonstrates intelligence, unless X is actually a meta-task involving skill-acquisition across a broad range of tasks.”

Generalisation is the heart of the criticism of current AI and benchmarks discussed so far. Informally, generalisation is “the ability to handle situations (or tasks) that differ from previously encountered situations”.

Generalisation can be system-centric or developer-aware. The former refers to situations in a developer designed test set, the latter includes “real world” situations beyond the developers knowledge. Chollet describes the spectrum of generalisation and recasts the history of AI as a climb from the least to most general. The four categories of generalisation given are:

- Absence of generalisation. These are systems with no uncertainty such as a sorting algorithm.

- Local generalisation, Robustness. Systems which can deal with new situations within a defined task. The advantage of early ANNs over their static program predecessors.

- Broad generalisation, Flexibility. Systems which handle situations not envisioned by the developers. This is the level that state of the art AI achieves today.

- Extreme generalisation. “adaptation to unknown unknowns across an unknown range of tasks and domains”. This is the ultimate goal of AI. Within this class is human-centric extreme generalisation which aims to “merely” capture the tasks/domain of the human experience.

Finally, Chollet reviews previous attempts to measure intelligence in humans, psychometrics. Chollet summarises the work both in the psychological literature and attempts to integrate the best parts of psychometrics into AI evaluation. Finally, Chollet looked to trends in broad generalisation AI which is overall negative about the lack of progress.

In summary, Chollet challenged us to examine our definition of intelligence and subsequently how we go about measuring progress in AI. The key concept is generalisation power, which is not explicitly measured in most benchmarks. Chollet sets the up the remainder of the work by outlining existing work from psychology in psychometrics which are designed to test general (human) intelligence.

A new perspective

In this part Chollet provides:

- The formal definition of intelligence using algorithmic information theory.

- A set of properties that a benchmark using this definition of intelligence should have.

Rather than regurgitating definitions and arguments from the paper I encourage the reader to consult the original work for the formal definitions. Instead I will try to summarise the intuition behind the formalism. The informal definition of intelligence Chollet uses is:

“The intelligence of a system is a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty.”

Skill-acquisition efficiency rather than skill should be the goal of AI developers. A system high in this measure is able to quickly adapt to new situations.

The system must have a limited scope of tasks. Chollet uses the no free lunch theorem to explain that an AI on the space of all possible problems would be no better than a brute force algorithm. Therefore to meaningfully be called intelligent some restrictions on the problem space are required. The task scope may be sufficiently broad (domain of human experience) that the intelligence can still be called “general”. When comparing intelligent systems there should be a shared task scope to make the comparison fair.

By limiting the task scope we can make use of priors. Priors are assumptions about the environment that have been encoded ahead of any experience. On the other hand, experience is gained through exposure to the environment (training in AI context). In humans, priors are innate cognitive faculties (e.g. spoken language) and learn new skills through experience (e.g. written language). Finally, generalisation difficulty is a property of a task which refers to how much behaviour has to differ from training in order to successfully complete the task. A system which can complete high generalisation difficulty tasks has made a good abstraction of the problem and is flexible enough to apply it to the new situation.

Using this definition of intelligence and subsequent measure it follows that: if two systems with similar knowledge priors that have a similar amount of experience differ in skill, then the system with higher skill is the more intelligent system. This is an improvement over current skill based benchmarks.

The intelligence definition is primarily concerned with information efficiency. In other words maximising task skill from limited experience. Chollet points out that there may be other desirable properties to add as “regularisation terms”:

- Computational efficiency. Real-time control requires fast processing. Some new situations may require fast learning (new dangerous situation).

- Energy efficiency. Particularly true for biological intelligence, but also needed to keep mobile robots operational for long periods of time.

- Risk efficiency Exploration behaviour is useful for discovering better approaches, but can sometimes be dangerous. The system should consider this trade-off.

On properties for a benchmark of intelligence. Importantly, in comparing two systems we can easily control for experience (on some new task), but controlling for priors is more difficult. The implication for this is that any benchmark of intelligence should explicitly describe the priors assumed by the test, and not be used to compare systems which do not meet these assumptions.

Furthermore, to control for “buying” experience the task set used in the benchmark should be as diverse as possible, and not be based on existing tests.

From psychometrics, the benchmark should attempt to establish external validity such that high performance in the test implies high performance in real wold tasks. Additionally, random elements of the benchmark should not meaningfully impact the result of the test, making it reproducible.

In summary, Chollet built on the analysis of the previous part to produce a quantifiable measure of intelligence which prioritises skill-acquisition over skill itself. The definition has implications for designing intelligence benchmarks which Chollet outlines. With the groundwork laid, Chollet now outlines an initial attempt at a new intelligence benchmark in the third and final part of the work.

A benchmark proposal: the ARC dataset

Chollet’s initial attempt at a new intelligence benchmark is the Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus (ARC).

The goals of ARC are:

- Implement the lessons learned from psychometrics while avoiding their limitations (for example reliance on skills such as reading/writing).

- Measure developer-aware generalisation by making some tasks unknown to developers of the test taker.

- Measure broad generalisation by using abstract tasks with few training examples.

- Explicitly describe the set of assumed priors to enable fair comparison of systems.

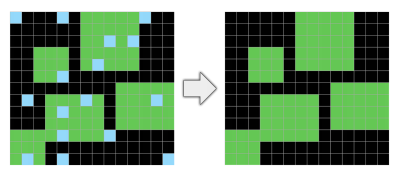

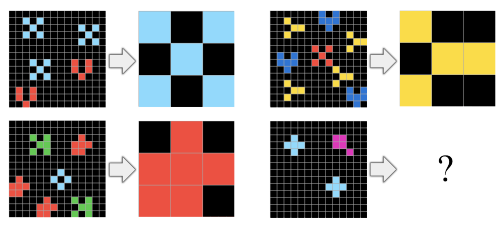

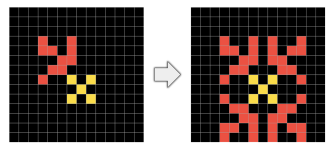

Tasks in ARC consist of variable sized input and output grids. The test-taker must analyse training input/output grids to determine the abstract rule used to generate the output. The test-taker has three attempts to create the correct output grid and receives a binary signal to indicate whether the solution is correct or not.

The priors assumed by the test are based on Core Knowledge from the psychological literature on human priors. Chollet describes this in full as motivation in the previous parts, and in this section provides examples of tasks which involve the priors used in ARC. The examples below are some of those given in the paper. Briefly, the priors are:

- Object cohesion (objects take up contiguous space), persistence (objects don’t disappear under noise or occlusion) , and contact (objects can touch)

- Goal directedness. Chollet points out that ARC doesn’t have a concept of time, but input/output grids could be modelled as start/end states of a process involving intentionality. The prior may not be needed, but may be useful.

- Numbers and counting priors, tasks use small numbers and involve counting/sorting objects.

- Geometry and topology priors. Lines and shapes. Symmetry, rotation, and translation. Scaling and distortion. Being in/out of a container. Line drawing and projections. Copying repeating objects.

In summary, ARC is a first attempt at a new kind of intelligence benchmark. ARC explicitly measures the kind of general intelligence we (humans) use, and it provides a new goal for AI developers to measure progress against. Chollet describes ARC as a work in progress, in fact constant update of ARC to add new tasks and features is expected. In the last part of the post I discuss what is next for this work.

Extensions and applications

Chollet identifies several topics of further work for ARC:

- Generalisation difficulty is used in the formalisation of intelligence but is not currently quantified for each task.

- Validity for the test should be established using a large human sample and comparing results to that of other valid tests.

- The dataset and diversity of tasks should be improved to ensure the test is not “gamed” by an AI test-taker. In other words, it should not be possible to hard-code or “buy” experience of tasks, but require good abstraction and generalisation.

- During evaluation a binary feedback signal is used. Chollet suggests that the test taker could interact with an “example generator” to request more granular feedback on a solution.

- The test is reliant on Core Knowledge priors. Understanding human priors is an open question, therefore ARC should evolve with this changing understanding. Furthermore, the implementation of these priors in ARC may be incomplete.

I would add the following personal open questions:

- How do we measure (in practice) the algorithmic complexity for priors, experience, and generalisation difficulty?

- How would the addition of the “example generator” improve the feedback signal to the test-taker? Does improving the signal come at a prohibitive cost of complexity in the “example generator”.

In this work Chollet is primarily concerned with measuring human-like general intelligence. While reading I was thinking about how current AI doesn’t achieve the kind of generalisation we see in even “simple” animals. Particularly in robotics. There are a number of useful applications (e.g. warehouse stock manipulation, package delivery) which don’t require the full human task scope to be “solved”. I think a great application of Chollet’s work would be to apply it to non-human intelligence benchmarks. One I found recently which could be an interesting candidate is the Animal AI Testbed. By using Chollet’s definitions we can avoid promoting “shortcuts” in our measure of progress, and promote developing flexible systems.

Thanks for reading, and thanks to François Chollet for a very well written step toward better AI.